Design principles such as SOLID or Composition Over Inheritance are abstract and can be hard to implement in practice, especially if you try to think them in before having any code. It takes practice working with them and many “mistakes” before getting them right. I reckon the difficulty lie in that it is an uncertain field and its correctness is not verifiable via static code analysis. Furthermore, there is usually more than one path to getting the result and bias towards these practices.

This post will not be about any principle in particular, but instead about how I apply those principle in practice, and more importantly when in the process of development I apply those practices.

Growing Your Software

As of late, I have been reading and watching much material that draws similarities between software engineering and gardening, more than architecting and building buildings. I subscribe wholeheartedly to that analogy as that very much describes how my process looks like. Enough of that analogy, I only ventured there to make a point:

Running code is alive, or need to be. It needs to grow into being

and it needs care. Once it has matured, it can live mostly by

itself, but when we start writing the code we know only little

of how it will look like in the end.

I for one have been fooled many times over by designing systems up front in order for priorities to be shifted mid-way. To mitigate this, I rigorously apply tracer bullets and the extreme programming practice of quickly punching a hole. This makes me stay agile, in the sense that changing directions is fairly easy.

Getting feature complete is a matter of iterative refactoring, which brings me to

Another Analogy

When working on a greenfield project, we do not have much to work with. It is a clean slate, but it is also a time of many insecurities. Usually, we have some sort of idea of what we are about to get ourselves into, we know enough to sketch a design or architecture.

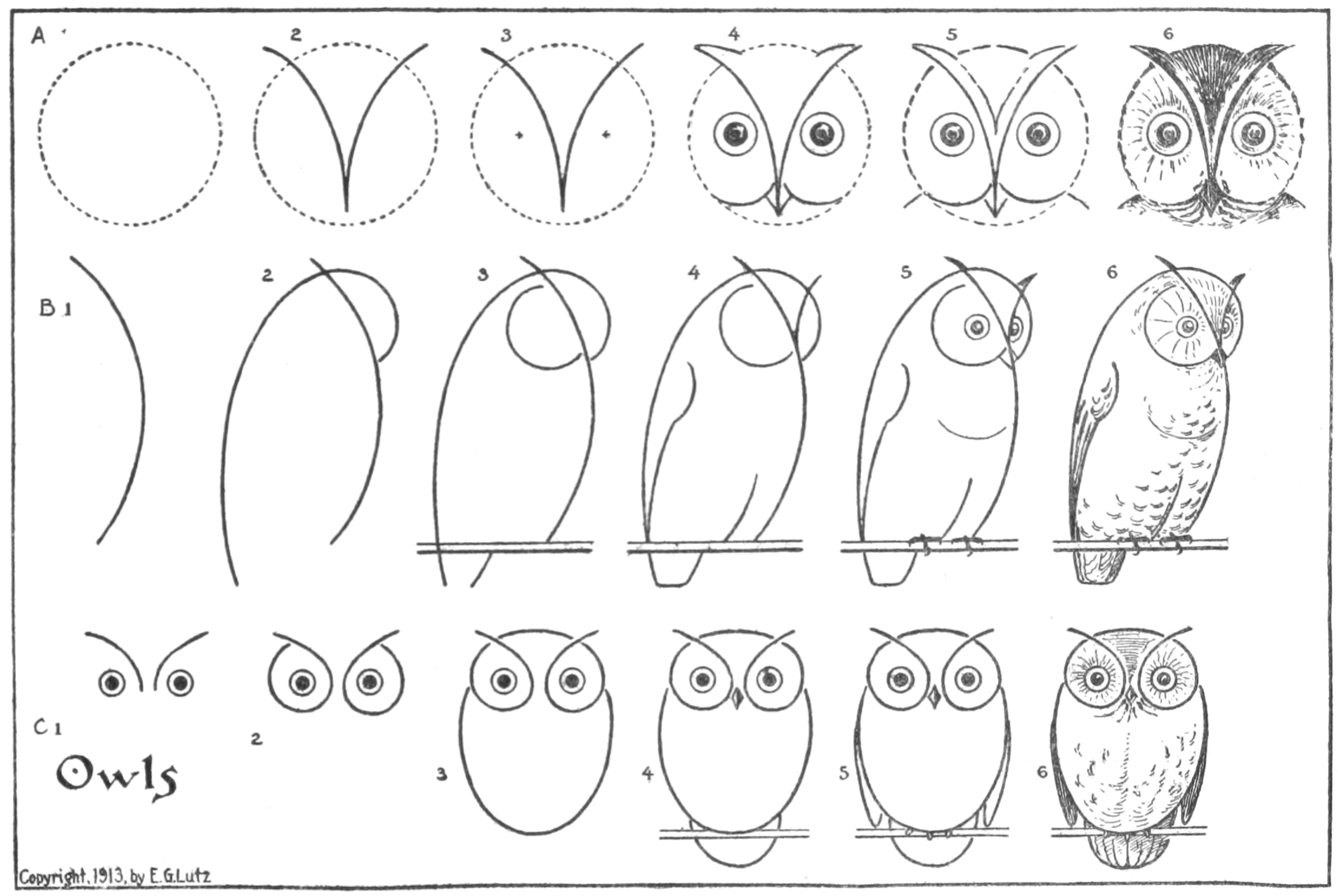

I sometimes draw, I think I am actually quite good at it using guides and everything. That makes me draw up (get it?) this analogy.

The initial sketch is good, we have a general idea of the main components that need to interact, where they will be placed - or at least a suitable place. So, stop analyzing and get to business, don’t worry about the principles just yet (wait, remember KISS and YAGNI here). Crank up the volume on your headset or whatever gets you going and get writing some code (also don’t forget your TDD practices, they’re going to be very important going forward.)

Oh, and NO DRYing. Everything should be WET/copy-paste at this point.

Welcome to round 2

Ok, you nailed that first user story! You punched a hole and you got a sunshine scenario working. It may be running on stilts, but the tests pass. (and by the way, if you did not write a complete end-to-end component integration test, now is the time to get back to your test-suite) - because we are now ready to refactor for great good – and refactoring means testing for regressions, constantly. Component integration tests ensures that you do not forget to update the interfaces between the already moving parts.

Waaait a second. Interaction between moving parts maybe calls for some design by contract?

But first, get those changes committed, reviewed and deployed.

Now, you are ready for your, first no-brainer refactoring. Get started on an interface that formalizes the structure between those component. You got yourself some tight coupling there so that part should maybe put into a shared library between the two components.

Don’t worry about having to deal with tests, you already wrote those. You maybe need to change the in and out on your components’ unit tests but your integration test should be steady as a rock - you’re just checking for regressions. If you find that you are starting to meddle with the component integration test, you’re overstepping your boundaries just now (except maybe for some renaming of imports)

There is a possibility that other smells accumulated. Personally, up to this point I have usually been somewhat inconsistent with naming (it takes me some working with code and terminology before getting it, almost, right… I never get naming right). In practice, I start removing abbreviations in variable names and make sure all methods are verb-phrases, all the code smells I can think of really.

With experience, you will know yourself well enough to know what you usually let lying around. Might as well take care of it immediately.

Also, DO NOT DRY yet.

Round 3

Time passed, you had a breather because the system needed to get running on the double, and then something else caught your POs attention… And you needed to fix this bug you left lying around in another system, and also your cat ate your commit, and…

Aaanyhow. At least you probably had a weekend or a chance to sit back and think about the mess you made thus far. And your PM calls you up saying “I got some new exiting task for you, and PO wants it yesterday for this customer demo who will cancel anyhow”.

Great, you got another task, and new requirements to draw some more lines – and maybe also start using an eraser. You can begin to see where the code is heading (ok, you probably already knew because the backlog accumulated like a waterfall thanks to PO/PM). Do yourself a favour and ignore it, they have just as little idea of what comes next. Because it is most likely going to be something that they haven’t thought up yet.

But this is good. Now we start getting a glimpse of the future of this code. Until now, we really just did some pre-germination or some sketching. Now it’s time to take a new pencil and start drawing some actual lines. (this analogy is really working for me!) You can start making plans for your code. And you have a very real idea of what you focus needs to be. It is the immediate surrounding of the lines (of code) or components that are making it into the changeset.

A word of caution, remember not to go full retard here. I have been caught here too many times myself thinking “is this SOLID? Ugh, which way does the composition arrow go? what do I need to do to get it just right?” Just don’t.

It is a waste of your time. Or, it is not a complete waste, but your time is better spent elsewhere so it is a waste of your employers time and your wild-ass-guesstimate is closing in on its due date. The important part is, your code is maturing, and it is solidifying (and maybe a little bit of SOLIDifying too?) which means you also start being able to make better judgments about the immediate future of the code, based on the lines you are actually changing.

If you are anything like me, you will also start identifying the pieces of the main code that really ought to be dragged out into subroutines, split up or rename components, ordering function arguments etc.

You may start DRYing now. But consider if things should not still be WET.

Rinse Repeat

This is it, it is this pattern iteration applied continuously to use ones best judgment and applying the boyscout rule ad-libitum.

Personally, I expect 2-3 major refactorings before I know where code is supposed to be loaded and placed. Then I start working on the details. Again, this is like when I draw, after drawing the guides, I work on the “main” lines and features. Draw those over and over to figure out exactly how they should be placed between one another. And when I got this sorted, I start working playing with the details.

For the code, it means that now it begins to make sense to start running down the checklist of your favorite principles and patterns to apply. One by one.

Stay agile

As a senior developer I have witnessed refactoring is something developers needs to be encouraged to do (especially if they did not write the code they are changing in the first place and they have no ownership). I regularly get “but it has already been reviewed” or “Let us do it some other time” when suggesting refactoring. I have a feeling the resistance is really due to it being seen as an admittance that “If I refactor, it must mean I was wrong the first time around and I don’t like admitting that”.

If that sounds like a familiar I hope it helps to remember that a garden is never perfect either, it is filled with living things requiring attention and it needs to be taken care of constantly. Sometimes, in order to grow, plants also need a little bit of time, or moved into or out of the shade. Sometimes they need to be trimmed, pruned, or nurtured. Some plants just die, some gets replaced for other reasons. In any case, the garden needs a caretaker or it will either overgrow or rot. Likewise will code.

I hope this inspired you. I know design principles can be hard to follow, not just understand, but also apply. This is written with the intention of giving some general pointers as to how a senior engineer goes about obtaining quality code. I am sure I have not managed to write down this process in full, and ask me in a year, and I would probably lay it out differently.

If you aim for perfect, you never get done. So just take one small step in the right direction, with each and every commit.

Summary

Design principles are great. I use them all of the time. But most importantly, I also know when in the process of development I should apply them.

- First iteration of a project or feature, only do the ones you got down habitually and simply “know” from experience is going to work. Focus on the business value, not the code.

- Second and third iteration, start identifying where the code is headed, where the “moving” parts supposedly are and get them isolated. Start clearing out smells as you get more intimate with the problem domain and its terminology.

- Ad-libitum, take care and clean the camp-ground - you will know when something starts to mis-align, and this is where you take a step back and refactor.

Recommended Reading

Litterature that makes the basis for my train of thought, or at least the teaching I recollect came from