Writing, Testing, and Documenting utility functions.

To me, utility functions are small bits of code that are DRYed as they are repetitive and does not relate directly to what the application I am writing does. It is more of a short-hand than anything else and I would otherwise have to write the exact same lines of code over and over.

If it relates directly to the application, I don’t consider it a utility function but an application of the clean code “functions should do just one thing”

def isoformat(dt: datetime):

return dt.strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S')

An example of a utility function. This is so generic that it is now part of the standard library

Utility functions usually “stand alone”, as they are not directly part of the

application logic, it makes sense to keep them boxed in a util library or

similar.

Even though they are defined for a particular part of the code, given the entire project works with the same problem domain, there is a considerable possibility it is re-usable elsewhere.

Testing

Utility functions are a very good place to practice TDD - you put something in and something comes out. Both ought to be simple and clearly defined. Utility functions, in my book, should rarely come with side-effects.

No doubt the function will be tested as part of an integration test for the application logic (right?).

However, from a maintenance point of view there is a possibility that the application logic will change or be removed from making use of that function. An observant developer would remove the utility function together with when making that change, but since it is added as a dependency. But, if there is no tooling to detect dead code, the likelihood of that utility function haunting the code-base after its utility has stopped is non-negligible. This in itself adds entropy, however when removing the application code, as a side-effect you also remove test-coverage of the utility function. Without separate tests, you get double up on code rot – in fact you get triple, because the knowledge of its utility is also removed.

Therefore, a utility function must always be tested separately from the application logic which is the main cause for its existence.

Altogether, when I add a utility method, I ensure to always include a separate unit test for that function.

def test_strftime_isoformat():

dt = datetime(1989, 11, 09)

assert strftime(dt) == '1989-11-09T00:00:00'

This conveys intent of the function to any other developer who might come by and think about changing anything. If not discouraging change, at least the expected interface is clear for the existing utilization of the utility function.

One might imagine a change

def isoformat(dt: datetime):

return strftime(dt)

def strftime(dt: datetime, fmt='%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S'):

return dt.strftime(fmt)

Notice how neither application logic or tests are changed.

Documentation

The only users of a utility library is other developers on the team. The best place to put documentation is in the source code.

This is the most likely place another developer would look for what a specific utility method does anyhow, is it not?

Finally, it will allow you to populate project documentation automatically.

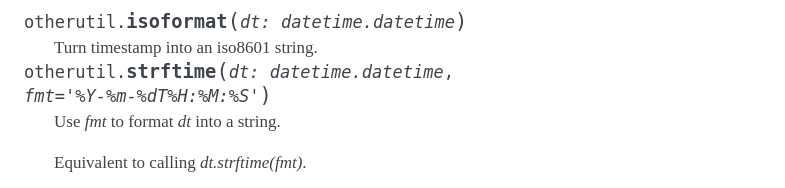

def isoformat(dt: datetime):

"""Turn timestamp into an iso8601 string."""

return strftime(dt)

def strftime(dt: datetime, fmt='%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S'):

"""Use `fmt` to format `dt` into a string.

Equivalent to calling `dt.strftime(fmt)`.

"""

return dt.strftime(fmt)

These utility functions are so simple that when looking at the code it does not bring any value. However, when generating documentation for the utility library you see some benefit.

(without a docstring, by default sphinx will not show you the function in the first place)

And of course, there is more to it.

Tests are Documentation

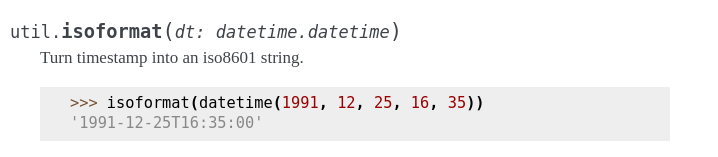

Nothing shows or documents the code better than tests, and python has a neat way of finding and running tests from within the function docstring. Meet doctest

You get to check that your code is correct and show how it works at the same time. After all, who remembers if ISO8601 has the T in it or not? And is Z required?

You also do your future self, and any other developer coming by, a one up by keeping the test right where the implementation is – we all have enough files open as it is, don’t we?

def isoformat(dt: datetime):

"""Turn timestamp into an iso8601 string.

>>> isoformat(datetime(1991, 12, 25, 16, 35))

1991-12-25T16:35:00

"""

return dt.strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S')

It is way more descriptive and readable than :rtype: str is it not? And you get

some neat formatting in your documentation too

Summary

-

Use utility functions for code of generic character. Detach them from the application code.

-

Be sure to treat the utility library and functions as stand-alone components.

-

The code in itself is of a generic character and may not show how it is intended to be used. Make sure to leave clues.

-

You can can code and test in one place, giving you documentation for free.

Appendix

Try out the module below with

python3 -m doctest -v util.py

from datetime import datetime

def isoformat(dt: datetime):

"""Turn timestamp into an iso8601 string.

>>> isoformat(datetime(1991, 12, 25, 16, 35))

'1991-12-25T16:35:00'

"""

return dt.strftime('%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S')